Sanders-Brown research shows clear connection between socialization, enrichment and brain health

Researchers from the University of Kentucky’s Sanders-Brown Center on Aging and the University of California Irvine are some of the first to show socialization and enrichment are good for aging brains.

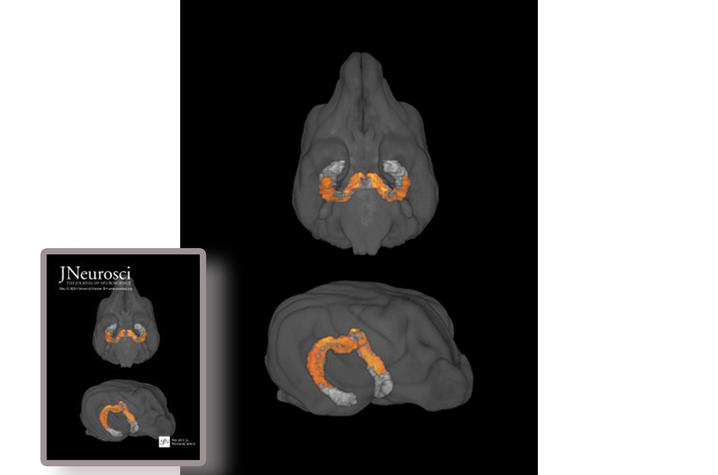

The collaborative study was recently published in the Journal of Neuroscience. Imaging from the work was so compelling it was chosen as the cover art for the issue.

The project began in 2019 with a $1.2 million grant from the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute on Aging. Researchers’ goal was to determine whether cognitive loss and other signs of neural dysfunction could be slowed down in aging dogs using drugs that reduce neuroinflammation and synaptic communication deficits.

“This study has great parallels to human health and disease,” said Chris Norris, Ph.D., one of the principal investigators of the study. He is a professor of pharmacology and nutritional sciences in the UK College of Medicine and Sanders-Brown faculty. “Staying socially connected, exercising and keeping your brain engaged with stimulating activities may provide substantial protection against the detrimental effects of aging and age-related diseases like Alzheimer’s.”

Synaptic communication deficits refer to problems in the way nerve cells (neurons) in the brain communicate with each other. Neurons send messages to one another through connections called synapses. If these connections aren’t working properly, it can lead to difficulties in how the brain processes information. This can affect various brain functions, such as learning, memory and overall cognitive abilities. These deficits are often linked to neurological conditions like autism, schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease.

“Dogs were chosen because they live in similar environments to humans, have similar metabolism and can perform complex learning tasks," said Norris. "Also importantly, beginning in middle age, some beagles develop Alzheimer’s-like amyloid plaques in the brain connected with cognitive loss — similar to humans.”

For the study, researchers worked with healthy middle-aged dogs that received daily oral doses of either a placebo or experimental drugs over three years. Nine years of age in a dog is comparable to 60 years in a human.

During this time, the dogs engaged in daily socialization with human caregivers and other dogs in a highly enriched environment that included toys, physical exercise and exploration.

The dogs were also routinely tested on several learning and memory tasks. They were assessed at the beginning of the study and then after each year of treatment researchers looked at the dogs’ brains using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), similar to what is used in humans to look at changes in brain size.

“Typically, what we see in both dogs and humans is that brains begin to shrink with old age, and especially with Alzheimer’s pathology. What we found really surprised us,” said Norris.

Contrary to what the researchers predicted would happen, the drug treatments had little effect on brain size during the study. But the surprise finding was that one brain region — the hippocampus — increased in size over the three-year period for nearly all dogs.

“This was very unusual. The hippocampus is critical to learning and memory and is one of the first brain regions to show structural and functional changes, including atrophy or shrinking, during Alzheimer’s disease,” said Norris. “The best explanation for why the hippocampus grew in our dogs was because of the high levels of behavioral enrichment and socialization they were exposed to.”

Though the research team was a little disappointed that drug treatments failed to affect age-related brain size measures, they were nonetheless excited about the data and believe the implications will be highly valuable to both the research community and the general public.

“Many of us are dog owners and we love our dogs!" said Norris. "Just like humans, dogs can develop cognitive deficits when they get older. They may pace around a lot, become confused, seem to forget where they are and some may show ‘personality’ changes. Our study shows that playing with your dog, providing regular exercise and social interactions with other dogs can help improve brain health, which could improve quality of life in your dog’s later years.”

The work is among the first studies to show beneficial effects of socialization and behavioral enrichment on the brain size in a mammal model with many similarities to humans.

Socialization, activity engagement and enriched environments are areas that researchers at Sanders-Brown often encourage when they hold workshops with the community and in conducting clinical trials with humans.

“Keeping your mind and body actively engaged in various activities, including socialization, exercise and cognitively stimulating tasks, can help keep the brain sharp as we age,” said Elizabeth Rhodus, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the College of Medicine and faculty at Sanders-Brown. “Whether it is a monthly dinner with friends, a new card club or volunteering for change, engagement and socialization are key ingredients to a long and healthy lifestyle.”

Rhodus is currently leading a clinical trial with individuals with moderate to severe cognitive loss and their caregivers which specifically addresses socialization, activity engagement and environmental enrichment. A recent participant caregiver acknowledged the importance of this type of research as she reflected on the notable changes she and her mother experienced.

“I’ve gotten far more out of it than I even dreamed I would,” she shared. “I feel like things have really improved the quality of our life and the quality of my life, and it’s been very good. [My mother] even sang… I have heard her sing, but it has been decades. She was singing to herself… when the song got done and she was done singing, she just laughed and laughed like she just had the greatest time. It’s kind of fun.”

Norris and the rest of the collaborative teams believe this research will have a direct impact on patient care even if it’s not in the form of a potential drug therapy. Socialization and behavioral enrichment are something all of us can do as we get older. It’s a highly practical, relatively inexpensive and non-invasive way to ward off the effects of aging and Alzheimer’s.

“It is something that’s been talked about before, but now we have clear proof of it. Bottom line is socialization, behavioral enrichment and environmental enrichment are good for your brain,” said Norris.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AG056998. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

More from this series Research Priorities - Neuroscience

Credits

Words: Hillary Smith (Public Relations & Strategic Communication)

Cover image: Jessica Noche