Research Isn't 'One Size Fits All'

We have all heard of, and perhaps purchased, clothing advertised as “one size fits all.” I’m not sure I have ever been happy with a purchase of clothing that was developed to fit everyone, the fit is not tailored, and in many instances downright uncomfortable. The same thing applies to using this approach to research. Unfortunately, for far too long, the male sex was the prototypical vehicle for experimental and clinical studies testing new drugs, devices and basic physiologic and pathophysiologic disease processes.

Females were excluded for reasons of practicality: the fluctuating hormones of a menstrual cycle might interfere with the research outcome, and it was often considered unethical to conduct biomedical research in someone who could become or was pregnant. It was assumed that if men showed benefit from a therapy, women would too, “one size fits all.”

Similarly, for decades research did not do enough to understand how issues of ethnicity, race, sex or gender — differences that were hard to study using basic experimental systems — are important variables that influence physiology, disease development and therapy.

Well, I am glad to report that research is changing, and at the University of Kentucky we embrace and focus on things that make us different from one another and how these differences influence health and disease.

A prime example is our focus on health disparities in the newly opened Healthy Kentucky Research Building. Kentuckians suffer from common diseases, like cancer, more than the rest of the nation. Why is this? Research within the Healthy Kentucky Research building focuses on differences, including those of race, ethnicity and geographic location, for example, that are important variables in the prevention, development and treatment of diseases that are entirely too common in Kentucky.

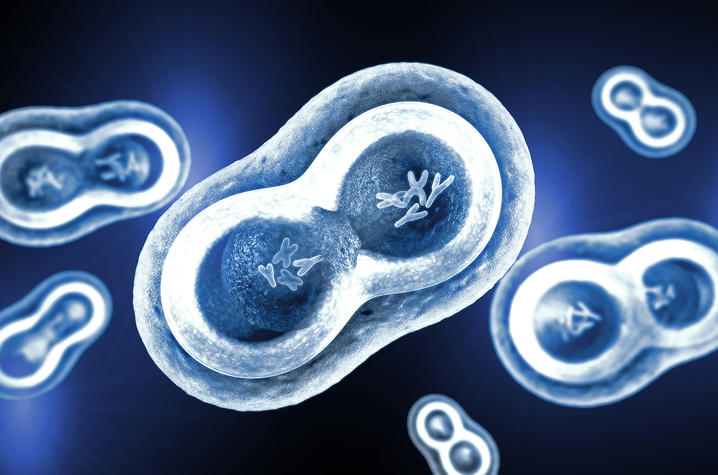

My own research program is a prime example of how we at UK strive to understand basic differences, like biologic sex, in the development of cardiovascular diseases. We use innovative experimental models to define the relative role of sex hormones, like estrogen or testosterone, versus genes that are on our sex chromosomes (XX for females, XY for males), in the development of vascular diseases. These major determinants of biologic sex (sex hormones and chromosomes) are studied as tools to develop therapies for vascular diseases that would work best for one sex or another. No more one size fits all!

As my program has progressed, I learned about Dr. Lisa Tannock, an endocrinologist working with transgendered individuals seeking gender affirming hormone therapy. I was particularly interested in understanding how the use of hormone therapy for the transgender population may influence long-term health, an area where new research is definitely needed. Dr. Tannock’s goal within the transgender clinic is to provide care that provides the best outcomes to each patient, with the lowest risk of harm, consistent with the Hippocratic oath which she took as a practicing physician, “First, do no harm.”

We are at the tip of the iceberg when it comes to understanding the diversity of humankind. With resources like the Healthy Kentucky Research Building at our disposal, UK researchers are poised and ready to consider diversity within all aspects of their research.

Credits

Dr. Lisa Cassis, Vice President for Research