New UK Research May Offer Hope for Alzheimer’s Patients

University of Kentucky Department of Neuroscience Professor Greg Gerhardt, Ph.D., hypothesizes that the balance of glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) — two main neurotransmitters in the brain — contributes to Alzheimer’s disease and age-related declines in cognition and memory.

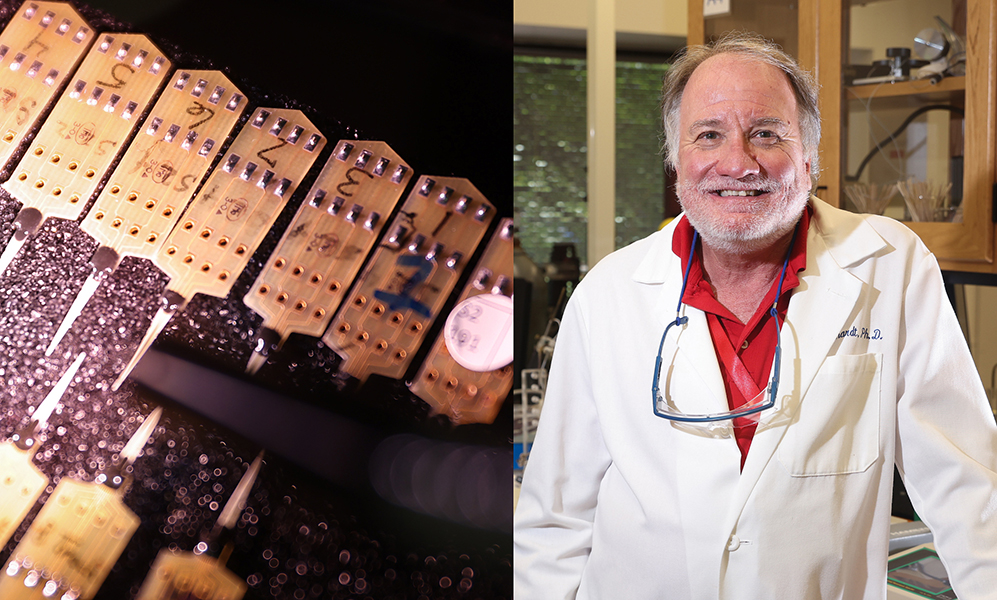

Now, the UK College of Medicine researcher and his team are about to find out. Gerhardt has developed new technology that can simultaneously measure the two neurotransmitters on a second-by-second basis. It is the first time this will be done in vivo — or in the living brain of awake animals.

Thanks to a five-year, $2 million grant from the National Institute on Aging, Gerhardt is launching a study to explore the balance of GABA and glutamate in the aging brain. The program will provide answers to long-standing questions that could help to develop new treatments for Alzheimer’s.

Gerhardt says it is a culmination of his nearly 40 years of brain research.

“This grant is based on brain recording technologies that my lab has worked on for decades. We now have the ability to measure these two molecules in vivo, which has historically been very difficult to do,” said Gerhardt, who directs UK’s Center for Microelectrode Technology. “We’re excited to go after some questions that the world is very interested in.”

Gerhardt, who has been at UK since 1999, studies the progression and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases, primarily Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s. To do so, he has developed intricate medical devices to measure signaling molecules in the brain. His research has helped scientists understand the difference between normal changes that occur in the brain with aging and the progression of such diseases. The understanding could lead to treatments to stop disease progression.

GABA, the brain’s main inhibitory neurotransmitter, lowers the activity of neural cells in the brain and central nervous system. Glutamate, the main excitatory neurotransmitter, increases their activity. Both play a critical role in memory development.

Gerhardt says GABA and glutamate counteract each other and that balance is important for normal brain function and memory. However, little is known about how that balance works, especially in the aging brain. In addition, prior studies that show irregular changes to the balance of glutamate and GABA in individual aging brain structures are ambiguous and often conflicting.

To oversee the study, Gerhardt is teaming up with UK colleague Paul Murphy, Ph.D., associate professor in the Department of Molecular & Cellular Biochemistry, who is one of the world's leading experts on animal models of Alzheimer’s.

The team will use Gerhardt’s enzyme-based brain recording technology to measure GABA and glutamate function in the brains of both normal aging mice and those with Alzheimer’s-like pathology and memory dysfunction. The device consists of a metalized microelectrode array (MEA) with enzymes that directly measure the two neurotransmitters in vivo.

The mice will then be tested for changes in spatial memory — the ability to remember different objects and their locations, and novel memory — the ability to identify new objects in an environment. Then their test scores will be compared to the glutamate and GABA level measurements to determine any potential correlations between neurotransmitter levels, behavior and brain pathology.

Gerhardt and his team are hopeful the study results will help in the future development of treatments for Alzheimer’s. Currently, there is no cure for the disease or way to stop or slow its progression. The only treatment options available ease symptoms.

“While there are currently FDA-approved drugs that change the way GABA and glutamate work, there is nothing available to address their balance,” Gerhardt said. “What if it could be adjusted in a safe fashion that would actually improve patients’ memory and slow the progression of the disease rather than just ease the symptoms? This study could become a significant step toward the development of such a treatment.”

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number RF1AG070952. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

More from this series Research Priorities - Neuroscience

Credits

Elizabeth Chapin (Research Communications)