Education Dean’s Latest Paper Focuses on School Finance Policy and Civil Rights

A newly published analysis of how dollars are distributed to schools in the U.S. posits that funding allocation models continue to disadvantage those in low-income communities, despite long-standing evidence that equitable funding is critical to students’ capacity to learn and achieve.

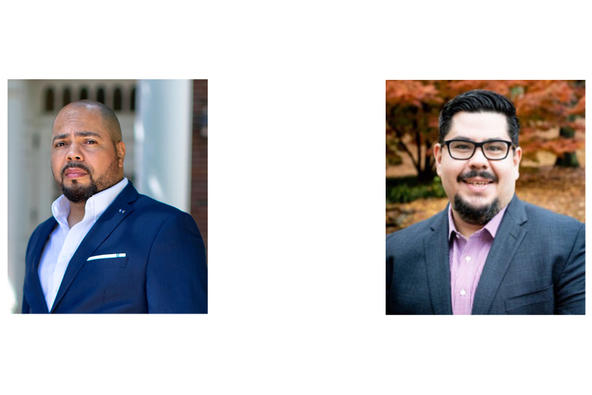

The article, authored by University of Kentucky College of Education Dean Julian Vasquez Heilig, Ph.D., and Davíd G. Martínez, Ph.D., an assistant professor at the University of South Carolina, appears in the latest issue of the Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality.

Due to the reliance on local property values to fund schools, property poor districts are prevented from increasing or equalizing school revenue to the level of wealthier districts. This poverty is unequally distributed across racial and ethnic backgrounds. Recent peer-reviewed research has shown that in gentrifying urban communities, as the proportional intensity of white students increases in schools, so do the resulting resources and demands for schools, the authors write.

“Education is a human right and a civil right, but our school finance policies are failing to treat it as such,” Martínez said. “Access to quality education is necessary for communities to thrive. When there are major educational disparities that exist between communities, it impacts everyone. This is demonstrably true if those educational disparities are predicated on community wealth, or race and ethnicity. Policy makers must do more to understand the history of school finance disparity in their community, and take steps to ameliorate its impact.”

Martínez and Vasquez Heilig say in their analysis that, despite countless attempts to reform school finance policy, the U.S. has historically been unable to improve school funding inequity and injustice. Without creating a more equitable system, resolving challenges for marginalized students will continue to be difficult.

“We looked at numerous studies showing increases in funding resulted in greater academic success for marginalized students. For instance, when more resources were put into majority LatinX urban schools, reading and math achievements increased,” Vasquez Heilig said. “Quite simply, money does matter and investing in education early and often matters in the everyday life of a student.”

The authors suggest federal policymakers adopt a framework known as Opportunity to Learn that would put in place a set of minimum standards for equitable learning in U.S. schools. These standards would include well-trained and certified teachers and administrators, timely curriculum and texts, up-to-date facilities and wrap-around services to support neuro-divergent learners and the health, nutrition, housing and family wellness of students. As a civil right, the authors argue for complete and differentiated levels of service for every student and funding that allows for the provision of those services.

After these standards for learning are set, it would enable state policymakers to raise revenue to proper levels of fiscal support for meeting the standards. The authors say this model deviates from past school reform and finance models that have focused on test scores and the need for increased student achievement. They, instead, support a model where success is determined by how policymakers are supporting high-quality educational access and availability in every community, promoting alternatives to the historical resource disparity that has oppressed BIPOC students and families.

“Ultimately, as a civil right, we need to support students through the P-20 pipeline, which includes high school completion and earnings later in life, with the ultimate goal of reducing adult poverty,” Vasquez Heilig said.

Credits

Amanda Nelson (College of Education)